On Wednesday morning, June 12, 21 guest workers at the King Fuji Ranch in Mattawa, Washington, didn’t file into the company orchards as usual, to thin apples. Instead, they stood with arms folded outside their bunkhouses, on strike and demanding to talk with company managers.

According to one striker, Sergio Martinez, “we’re all working as fast as we can, but the company always wants more. When we can’t make the production they’re demanding, they threaten us, telling us that if we don’t produce they won’t let us come back to work next year. We want to speak with the company, so we’re not working until they talk with us.”

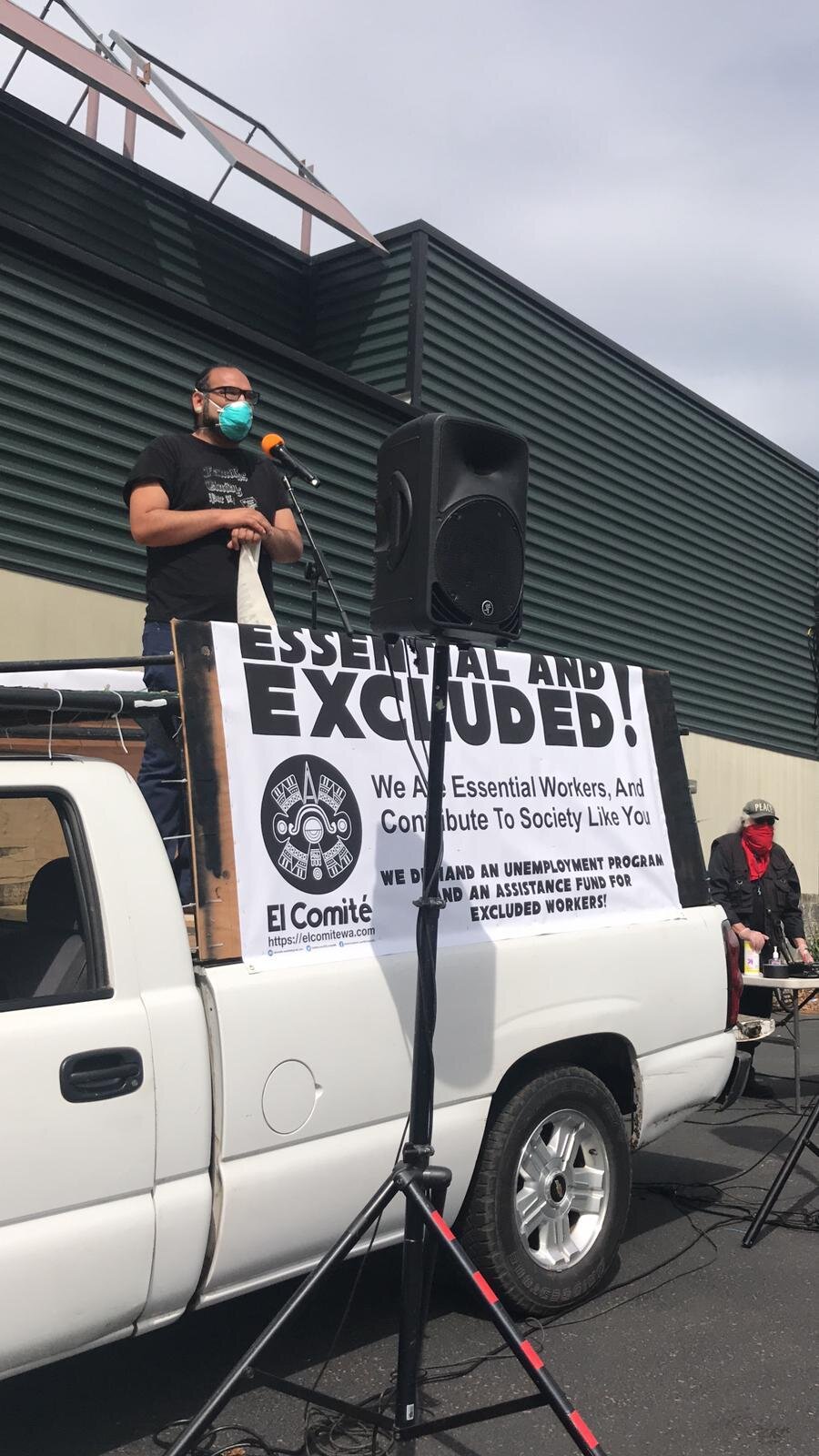

Martinez and his friends have joined a labor upsurge among both H-2A guest workers and Washington’s existing immigrant farm labor workforce, which has forced its state legislature to take action to protect both. New York state has just acted to increase the labor rights of farmworkers as well. Meanwhile, California, while it’s made important advances, has yet to enact similar legislation.

Martinez voiced a complaint common among H-2A guest workers. Pressure to work harder and faster is permitted by the U.S. Department of Labor—indeed, often written into the certifications that allow growers to import workers. The job order approved by the Labor Department for King Fuji Ranch, for instance, lists the first reason why a worker can be fired: “malingers or otherwise refuses without justified cause to perform as directed the work for which the worker was recruited and hired.” If a worker’s productivity doesn’t improve after “coaching,” then “the Worker may be terminated.”

“Coaching” at King Fuji, according to Martinez, means “they threaten to send us back to Mexico.” Another worker, who preferred not to give his name, explained that “they give you three tickets [warnings], and then you get fired. They put you on the blacklist so you can’t come back next year. Workers who were fired last year aren’t here this year.”

The contracts under which workers come to the United States in the H-2A agricultural guest worker visa program allow employers to set production quotas. They can fire workers for any reason, and fired workers can no longer stay in the country. In effect, getting fired for low productivity makes a worker subject to deportation. Employers and their recruiters are allowed to maintain lists of workers who are eligible for rehire, and of those who are not—in effect, a blacklist.

The impact of this power imbalance has produced a long train of complaints of abuse. That not only led to the King Fuji workers’ strike and others like it, but also convinced the Washington state legislature to pass a new law that seeks to enforce greater protections for workers.

In February, a group of workers at the King Fuji Ranch first contacted the new union for farmworkers in Washington state, Familias Unidas por la Justicia. Union president Ramon Torres and Edgar Franks, an organizer for the farmworker advocacy organization Community2Community, went to Mattawa to talk with them.

Franks says the workers were scared, but upset over their working conditions. “It was freezing and they couldn’t feel their feet or hands,” he said. “Some workers had pains in their arms and hands, but were afraid to go to the doctor because they might get written up, and with three written warnings they’d be fired.” The company required them to thin between 12 and 15 sections per day, which workers said was an impossible demand.

Workers listed other complaints as well. They had to pay for their own work gear, including $60 for work boots. They didn’t get paid rest breaks. Both are violations of the regulations governing the H-2A program. Franks and Torres were told that when workers were hired they signed an eight-page contract in English, a language they neither read nor spoke.

The two organizers explained labor rights to the workers, and agreed to stay in touch. In May, workers called Torres and Franks, asking them to come help organize a work stoppage. “They told us,” Torres recalled, “that managers had begun giving them grades like in school—A, B, C, D, and F—according to how much they produced. Workers in the F category would be sent back to Mexico, and wouldn’t be hired again next year. A lot of people were frightened by this threat, but 20 decided to act.”

“We even have bedbugs, and now they want to grade us on how clean our barracks are,” Martinez fumed. “At work, some of the foremen shout at us, and accuse us of not working well or fast enough. And when we do work fast, they cut the piece rate they’re paying us so we can’t earn as much.”

Wage cutting and work pressure are both hallmarks of the H-2A program. Companies using this labor-contracting scheme must apply to the U.S. Department of Labor, specifying the living conditions and the wages workers will receive. Each year, the federal government sets, state by state, an Adverse Effect Wage Rate—the wage that growers must pay H-2A workers. It is set at a level that supposedly won’t undermine the wages of local workers, but it’s usually just slightly above the minimum wage. In 2019, the AEWR wage in Washington increased to $15.03 from $14.12 in 2018. Washington’s minimum wage went to $12.00 this year, and will go to $13.50 next year.

On January 8, however, the day before the new H-2A wages were to go into effect, the National Council of Agricultural Employers, a national lobbying organization for U.S. growers, filed suit against the U.S. Department of Labor to roll back pay to 2018 levels. Michael Marsh, NCAE president and CEO, said the increases were “unsustainable,” and would cost growers “hundreds of millions of dollars.” The suit was dismissed in March, but, Marsh said, “we clearly understand the devastating consequences to farm and ranch families of a mandatory wage rate unconstrained by market forces and we had to act.”

The impact of market forces on farmworker wages has been devastating, and affects far more than H-2A migrants. According to the Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey, there are about 2.5 million farmworkers in the United States. About three-quarters were born outside the country, and half are undocumented. Farmworker Justice, a Washington, D.C., farmworker advocacy coalition, says the average family’s yearly income is between $17,500 and $19,999. A quarter of all farmworker families earned below the federal poverty line of $19,790.